Werner Heisenberg and Jewish Science: Part I

/Bavaria is a land of lakes and mountains. The Koenigsee is a good example of what I mean. There is a beach here and there, but for the most part the mountainsides plunge directly into the lake. Steep banks mean deep waters, and the Koenigsee is no exception to the rule. The lake is almost as deep as the mountains next to it are high. The water is so clear—the boats near the shoreline seem to be floating on air—that you think you could see all the way to the bottom, but the bottom of the lake is a long way down—623 feet, to be exact—which makes it three times as deep as Lake Erie, one half the depth of Lake Superior, and 300 feet short of Lake Michigan at its deepest. The drama of the Koenigsee comes from its contrast with its surroundings because although it is almost as deep as Lake Michigan, it covers only two square miles, as opposed to the 31,000 square miles which Lake Michigan covers.

So, God made the Koenigsee dramatic, but the Bavarians turned it into a work of art. The best way to appreciate this is to approach St. Bartolomew’s Church at the far end of the almost five-mile long lake by electric boat, which is the way most tourists do. The boat’s electric motor ensures that the water remains drinking-quality pure, but the Church organizes and focuses the surrounding landscape in a way that does not happen at Lake Michigan. Shortly after returning from Bavaria I took an Indian friend to Warren Dunes State Park and climbed Tower Hill, a large sand dune on the lake’s western shore. On a clear day you can see the skyscrapers of downtown Chicago from the top of Tower Hill if you look to the southwest; on this day in late October, the only humans structure we could see was the miserable bunker of toilets which the State of Michigan built between the sandy shore and a lake of asphalt created to accommodate the hordes who show up there on sunny Sundays in the summer. The toilets didn’t work in the previous miserable bunker and something even less elaborate—sans snack bar—was all the chronically bankrupt state of Michigan, home of America’s once powerful auto industry, could afford.

America, I told the audience to the speech I gave in Bavaria the day after my companion and I sailed along the Koenigsee, is a country that went from barbarism to decadence without discovering civilization along the way. The toilet bunker at Lake Michigan is a good example of that, especially if you take note of the bathing suits the ladies are wearing after they emerge from changing in the toilet stalls. But Oklahoma City, which went from cattle drives down main street in the 1950s to celebrating a “Drag Queen Christmas” in 2018, is another good example. Not even notoriously decadent Berlin would dare something that blasphemous, and Berlin, for the geographically challenged, is not in Bavaria.

America has beautiful nature, and it has a culture, of sorts, but it never figured out how to bring the two together into one harmonious whole. The beautiful cities America once had were wrecked by highwaymen like Robert Moses, who in spite of immense political influence, failed to integrate Manhattan and the automobile, because even Robert Moses could not do the impossible.

In Bavaria nature and culture are complementary; in America they are antinomies. In the years I have spent traveling this globe, I have found no other spot on earth where nature and culture combine more successfully than in Bavaria. The Koenigsee is one of the best expressions of that successful combination. The toilet bunker at Warren Dunes is just one local expression of America’s failure. The best national expression would be the Appalachian Trail, whose principle seems to be that man and nature are natural enemies and man’s culture, therefore, must be kept as far from “nature” as possible because of man’s natural depravity and his propensity to destroy nature whenever he comes in contact with it. You can wander for over 2,000 miles under forest cover and over mountains on the Appalachian Trail without ever encountering a restaurant, even though highways are invariably near.

Bavarians, on the other hand, have figured out how to place restaurants at the top of mountains without destroying the reason people came to the mountain in the first place. If you climb the mountain that separates the Tegernsee from the Schliersee, you will find a restaurant at the top—two, in fact—and neither offends the area it occupies, largely because neither has a parking lot. If you want to eat at these restaurants, you have to walk there. Berggasthof Neureuth isn’t a magnificent baroque church like the one that crowns the far shore of the Koenigsee, but it’s a great place to have a meal after you’ve worked up an appetite by climbing the mountain to get there. In America you can enjoy the view from the top of the mountain while nibbling on granola bars and sipping freeze-dried coffee, if you brought your own primus stove to heat it. There is a snack shop and parking lot at the top of Pike’s Peak. In Bavaria it is difficult to find a mountain without a restaurant where you can get a decent meal.

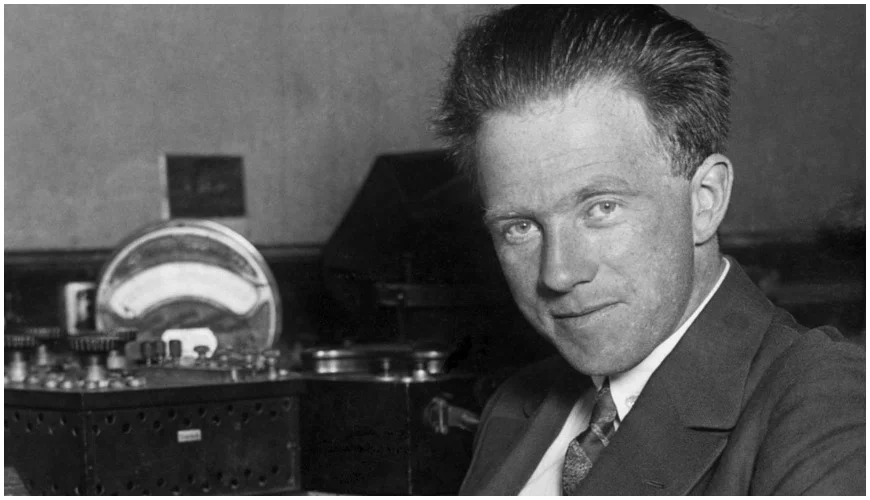

On a clear day, you can see the Walchensee from the summit of the Herzogstand. The Walchensee may or may not be as scenic as the Koenigsee, depending on your point of view, but it is in many ways more important culturally. Lovis Corinth, a transplanted northern German who found Bavarian soil more congenial to painting than his native Prussia, did landscapes of the Walchensee from the terrace of his house just above the town of Urfeld on the shores of that lake. In the spring of 1939, Werner Heisenberg, the German physicist who had won the Nobel Prize in physics in 1932 for discovering quantum mechanics, “went in search of a house in the mountains in which my wife and children could take refuge from the coming disaster.”1 He eventually found “just the right place in Urfeld, above Lake Walchen, a few hundred feet up from the road on which Wolfgang Pauli, Otto Laporte, and I had gone cycling so many years ago, discussing quantum theory while looking across the Karwendel mountains. The house had belonged to the painter Lovis Corinth, and I had admired the view from the terrace at exhibitions.”2 In his speech commemorating the 800th anniversary of the city’s founding, Heisenberg described Munich as a place where “it was not unusual” for his physics teacher Arnold Sommerfeld “to sit with the painter Corinth, who also came from East Prussia, and have a cup of coffee and discussion with younger physicists.”3

Werner Heisenberg was born in Wuerzburg on December 5, 1901. When he was eight years old, his family moved to a flat in one of the large apartment buildings in Schwabing, Munich’s Greenwich Village. Deprived of nature, young Heisenberg discovered culture, which meant the piano, classical languages, and mathematics. His career as a physicist came about as a result of accident and the influence of the Zeitgeist. When Heisenberg the undergraduate told Ferdinand von Lindemann that he had become interested in mathematics because of reading Hermann Weyl’s book Space, Time, and Matter, Lindemann informed him, “In that case you are completely lost to mathematics.”4 As a result Heisenberg went on to study physics under Arnold Sommerfeld, then head of the Faculty of Theoretical Physics at the University of Munich at a time when “theoretical physicists” were “the 20th century’s real philosophers.”5

Heisenberg was a flower which bloomed from a culture which had deep roots in Bavarian soil and could have grown no place else in the world. He came by theoretical physics naturally because his father taught middle and modern Greek at the University of Munich, 6 giving him the benefit of a classical education which allowed him to read Plato in the original Greek on the roof of the Theological Training College in Munich, as that city descended in the anarchy which followed the establishment of the Bavarian Soviet Republic in 1919. It was his study of Greek which first introduced him to the concept of the atom, and it was his reading of Plato’s Timaeus which opened his eyes to the possibility that the atom might not be material. Plato’s explanation of the atom as form instead of a very small chunk of matter prompted Heisenberg to ridicule the description of atoms in his Gymnasium physics book, which described them as possessing “hooks and eyes,” which allowed them to link up with each other to form molecules.

Under the thousand-year tutelage of the Catholic Church and the Benedictines, Bavaria had become a work of art, and it was the congruity between the mind and nature which Heisenberg found there which enabled him to overcome the deadening distinction between the res cogitans and the res exstensa which Rene Descartes had decreed centuries before, thereby sending both philosophy and science off in the wrong direction to this day. While hiking around the Starnbergersee, another Bavarian lake, Heisenberg came to the conclusion that: “the same organizing forces that have shaped nature in all her forms are also responsible for the structure of our minds.”7 If by Logos we mean rationality as it exists in the mind of God and not as it existed in the radically bifurcated mind of Rene Descartes, Heisenberg discovered Logos while hiking in Bavaria. His wife claims that during times of stress, Heisenberg would “retreat into the mountains; skiing and hiking were his irreplaceable means of relaxation.”8

[…]

This is just an excerpt from Culture Wars Magazine, not the full article. To continue reading, purchase the January, 2019 edition of Culture Wars Magazine.

Read More:

Culture of Death Watch

50 Shades of Libido Dominandi - Jesse Russell

Owner of a Lonely Heart - Mischa Popoff

Dead Letter Office - John Beaumont

Features

Werner Heisenberg and Jewish Science Part I - E. Michael Jones

Reviews

Canevas de Method de Deradicalisation - Reviewed by Anne B. Gardiner

Jurassic World: Fallen Kingdom - Reviewed by John Tuttle